James Karales

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

James Karales

James H. Karales, the photojournalist whose 1965 picture of determined marchers outlined against a lowering sky became a pictorial anthem of the civil rights movement, died on Monday. He was 71. The cause was cancer, his wife, Monica, said.

A resident of Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y., Mr. Karales was a staff photographer for Look from 1960 until that magazine closed in 1972. He documented pivotal events of that tumultuous era, notably the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. While many photojournalists trained their cameras on the brutally confrontational, Mr. Karales often took quietly sober pictures that, the critic Vince Aletti noted in The Village Voice, had ''the weight of history and the grace of art.'' To study Mr. Karales's iconic picture of the march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery is to appreciate the power and poetry that he packed into a seemingly casual picture. Leading the march, and setting its tone, are two young men and a young woman, all in shirts and dark pants and striding in step. There is a scattering of Stars and Stripes. But as if hinting of what is to come, the sky is a huge mass of dark clouds. Mr. Karales was born on July 15, 1930, in Canton, Ohio, to Greek immigrants and planned to be an electrical engineer when he enrolled at Ohio University. That changed the day he saw what his roommate, a photography major, did in the darkroom, Mrs. Karales said. He switched his major to photography. With a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1955, he went to the Magnum photo agency in New York and became the darkroom assistant to the master photographer W. Eugene Smith. Mr. Karales was housed and fed by the Smith family and worked without pay, Mrs. Karales said. His two-year stint left a permanent mark on him. He became a first-rate printer, producing velvety shades of gray and black. Like Smith, he underscored the human dimension in even his most harrowing pictures. And like Smith, he immersed himself in the subjects of his photo essays. After his time with Smith, Mr. Karales documented life in Rendville, Ohio, a mining town that was one of the few integrated communities in America in the late 1950's. He showed his picture essay to Edward Steichen, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who bought two of the images for that museum's collection. Helen Gee gave him his first solo exhibition in 1958, showing his Rendville pictures at her Greenwich Village gallery, Limelight. That same essay drew the attention of Look's photography editor and landed Mr. Karales a job there. After Look closed, Mr. Karales became a freelance photographer. Mr. Karales's first marriage ended in divorce. In addition to his wife, Monica, he is survived by four sons, Joseph, of Cortland Manor, N.Y.; James D., of Cold Spring, N.Y.; Alexandros and Andreas, of Croton-on-Hudson; three grandchildren, and a brother, Nikos, of Canton, Ohio.

Unlike other noted photojournalists of his era, Mr. Karales's name and work -- other than his picture of the marchers -- remain little known, and no book of his work has been published. Mr. Karales was modest and unaggressive to a fault, said Howard Greenberg, who gave Mr. Karales his first major exhibition in his New York gallery in June 1999.

Civil Rights, One Person And One Photo At A Time

The hands of the father and his young daughter wave emphatically: the two are not in agreement. The man talks. His eyes are closed; he looks pained. The child listens, but gazes at a plate of cookies on the dinner table.

The scene is not unusual: a father is telling his daughter that she will not be going to an amusement park. But he is doing so not because it is a school day, or because he is punishing her. He fears for her safety.

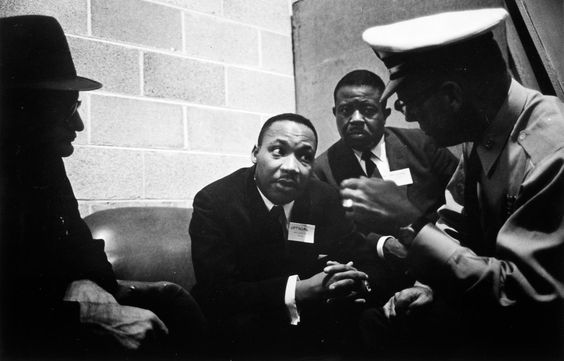

The father is Martin Luther King Jr.; the child is his 7-year-old daughter Yolanda; and the two are engaged in a conversation that no parent wants to have. He is explaining to the girl for the first time the hazards of segregation and the reasons she cannot visit Fun Town, a popular but restricted theme park in Atlanta.This photograph, (Slide 6) which first appeared in a 1963 photo essay in Look magazine, is emotionally intimate and psychologically insightful, like many of the images in “Controversy and Hope: The Civil Rights Photographs of James Karales” (University of South Carolina Press). The book, by Julian Cox, provides a singular opportunity to re-evaluate the innovative work of Mr. Karales, who died in 2002, at age 71.

As Dr. King’s aide and confidante Andrew Young notes in the book’s foreword, Mr. Karales’s photographs were distinguished by their ability to reveal the “complexity of emotions intertwined with the hopes and hardships of the struggle.” Their personal, contemplative approach was not always in step with a mainstream press enthralled by the high drama of historic speeches, conflagrations and demonstrations. This approach may also have been the reason Dr. King, who was fiercely protective of his family, granted the photographer unprecedented access to them.

Mr. Karales typically favored the individual over the collective, and his photographs are more like artful portraits than the straightforward documentation of momentous events. In his reporting on the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights in the spring of 1965, for example, he frequently photographed participants — the famous and the unknown — up close, carefully rendering their individuality and state of mind.

His images of the march resonate with nuances of emotion and psychology: a tight, brooding shot of a young demonstrator in profile; the bitter, scowling face of a segregationist being arrested (Slide 16); a black child nestled contently on the shoulders of a bearded white man (Slide 11); the indelibly memorable photograph of an African-American teenager staring wearily into the camera (Slide 12), the word “vote” emblazoned on his whitewashed forehead.

This intimate viewpoint aligned Mr. Karales more with the strategies of the black press than those of the mainstream media. Just as the mainstream media dispensed profiles about white people — relegating people of color to stereotypical, sensationalistic or communal reporting — publications owned and operated by African-Americans covered the private lives of the ordinary and famous alike.

These profiles, accompanied by photographs or drawings, were the mainstay of one of the earliest black pictorial magazines, The Crisis, edited by the civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois. In the civil rights era, the profiles continued to have a central role in the periodicals of the Johnson Publishing Company — Ebony, Jet and Tan, the first black women’s magazine — subtly challenging the status quo by emphasizing, rather than concealing, African-American humanity, individuality and psychological nuance.

If Mr. Karales’s method was akin to that of the black press, it was driven not by sympathy — the motivation Mr. Cox ascribes to it — but by empathy. Born into an immigrant Greek family in Canton, Ohio, in 1930, Mr. Karales struggled to learn English. He experienced firsthand the hardships of a community routinely viewed as exotic, inferior and not quite American. After working blue-collar manufacturing jobs, he enrolled in Ohio University and studied photography.

Mr. Karales was determined to use his camera in the service of social justice. From his first photo-essay — a tender, keenly observed profile of Canton’s working-class, Greek-American community (above) — he strove to reveal the complexity of his subjects by stressing the individual details lost amid collective stereotypes and biases.

Over a half-century career, including a staff position at Look that gave him a national platform, Mr. Karales continually fixed his lens on the marginal, the besieged and the politically fraught: coal miners in the racially integrated but economically depressed town of Rendville, Ohio; racial discrimination in organized religion; the quagmire of the Vietnam War; and segregation in New York City. (Those last photographs went unpublished, perhaps because they upended the era’s myth of Northern racial tolerance.)

Nowhere is Mr. Karales’s defiance of racial clichés more apparent than in his 1960 Look profile of Richard Adams, a pioneering speech therapist and social worker. The photo-essay inverted racial typecasting: Adams was black, his students were mostly white, and they coexisted not in a Northern city but in rural Iowa. These images of adoring youngsters and their dedicated teacher spoke to the possibility of racial harmony. But they also called into question an abiding myth of integration: that African-Americans had the most to gain from it.

Mr. Karales’s focus on the individual succeeded — paradoxically, as Mr. Cox notes — because it added to his work “some sense of a common, shared humanity.” By affirming our fundamental similarities, his images implored Americans, in an age of turmoil and transition, to re-examine their own humanity. Rather than presenting predictable scenes of racial disunity, they challenged a nation to face the individuals it had reduced to collective symbols of fear, condescension and hate. There, in the midst of crowds and chaos, he found one person, one image.

Maurice Berger is a research professor and the chief curator at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and a consulting curator at the Jewish Museum in New York. He is the author of 11 books, including a memoir, “White Lies: Race and the Myths of Whiteness.” He curated a show, “For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights,” and contributed essays to “Gordon Parks: Collected Works” (Steidl, 2013)